By: Liliana Silva-Vazquez

As I examine this painting and revisit Lady Montagu’s 27th letter, I see many parallels between the internalized male gaze, the explicit/implicit misogyny people hold, and the danger of seeing a particular event through a male-dominated lens. With that, I think Lady Montagu has a conflicted point of view because of her internalized misogyny and her radical ideas on how free the Ottoman Muslim women are compared to English women.

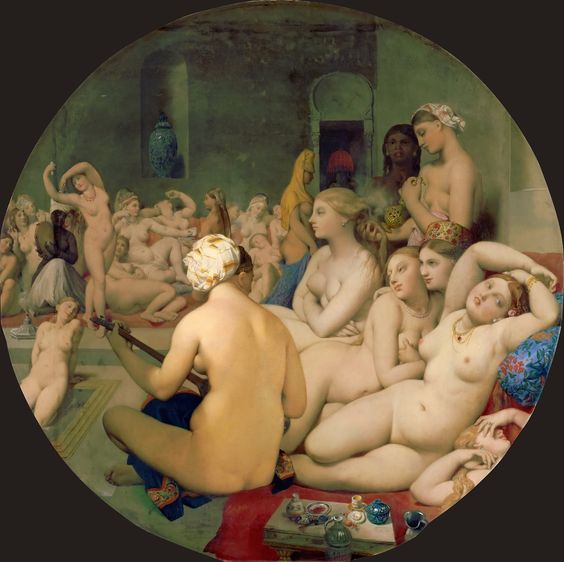

The first thing I noted as I looked at the painting was the overexaggerated male gaze. The women are lounging in very dramatic ways that seem to emphasize their lustful appearances with every twist and turn of their bodies. Their faces are either completely hidden like the woman who has her back turned to us or only show their side profiles so that our focus is on their bodies and not their faces. This contributes to the objectification of women and Lady Montagu had a similar view when she stated, “the truth of a reflection I had often made, that if it was the fashion to go naked, the face would be hardly observed” (102). Here we can see how she contributes to the objectification of women’s bodies. She also comments even further on the ridiculous beauty standards of women when she says, “I perceived that the ladies with the finest skins and most delicate shapes had the greatest share of my admiration, though their faces were sometimes less beautiful than those of their companions” (102). In this section, she not only reveals her internalized male gaze but also her internal misogyny that taught her to value beauty over everything. This is especially important to note because, in England, the men did not want to see the silhouettes of their women either so a “pretty” face was highly valued and sought after and just the thought of a group of naked women together calls for a burning. So, I do not see any women in the painting looking “natural,” they are all dramatized and even pictured holding one another intimately which contributes to the fantasized male accounts of these bathhouses. The lighting was also very telling of what the painter may have been thinking as it is very dark when in reality, Lady Montagu said, “with no windows but in the roof, which gives light enough” (101). This darker shading could signify the “seductive,” “lustful,” or even “shameful” views of the bathhouse because having a group of women in a secluded space means there must be some sort of sexual tension or experiences within from a male-centered POV.

In conclusion, everyone can have the male gaze internalized as well as implicit/explicit misogyny, but depending on the person’s will to change, their views may just be complicated and not absolute. Even though there is an obvious danger in seeing everything through a male-dominated lens, change does not happen overnight; it is up to us to create more meaningful paintings of feminine entities and to tell the truth through our stories as Lady Montagu has attempted.