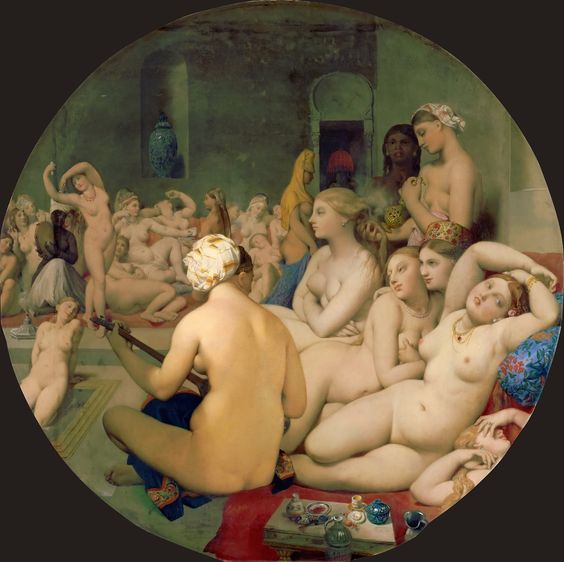

“I fancy it would have very much improved his art to see so many fine women naked, in different postures, some in conversation, some working, others drinking coffee or sherbert, and many lying on their cushions, while their slaves (generally pretty girls of seventeen or eighteen) were employed braiding their hair in several pretty manners” (Montagu 102). On its face, there’s not much to differentiate Montagu’s vision of the Turkish bathhouse from the painter’s vision of it. However, what sets it apart is the focus of these two visions. In the painting, the bottom right woman is posing, as if showing off her body to an unseen lover, implied to be a man. Next to her is two women holding each other the ways lovers might, one of whom is also employing a seductive pose. It subtly puts forth a sexualized interpretation of the bathhouse, built for a man’s imagination and consumption.

In contrast however, Montagu’s image of the bathhouse is markedly different. “So many fine women naked, in different postures, … conversation, … working, … drinking coffee or sherbert” puts for a more simple image of women doing typical things of leisure and work whilst naked in a bathhouse. Other than the word “naked” there is no language to imply anything sexual or seductive. What’s also interesting is that Montagu is also putting forth a male gaze in this passage, but one that isn’t sexually consuming in nature, but rather, utilitarian. “I fancy it would have very much improved his art” is a far cry from a sexualized male gaze and is rather just another gaze within the bathhouse to contrast her own. It is a gaze she puts forward to capture the beauty of the moment she sees. Women within their own space without worry or care.

-FM Radio